http://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/04/sports/baseball/04kepner.html

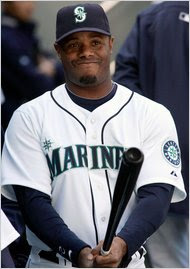

A Baseball Natural Just Wanted to Be Normal

TYLER KEPNER

June 3, 2010

His name and his talent forged a destiny for Ken Griffey Jr. He was going to be famous, whether he liked it or not. Yet in many ways, Griffey, who retired on Wednesday after 22 major league seasons, simply wanted to be normal. The inherent contradiction is part of what made him as fascinating a person as he was a ballplayer.

And let’s make no mistake: from 1989 through 1999, with the Seattle Mariners, Griffey was truly incandescent. He oozed potential and lived up to it. The choices his contemporaries made in the steroids era have saddened or angered so many fans, yet Griffey stands apart. He was the best of his day, no asterisks needed.

At this point, a reporter is obligated to note that we can never be sure who was clean. O.K., fine, but with outrageous physical gifts inherited from an All-Star father, Griffey was naturally dominant. There was no motivation to cheat; he was not jealous of other stars, like Barry Bonds, or insecure about his place in the game, like Alex Rodriguez.

I also think he was scared of taking steroids. Griffey told me last year he has never once been drunk. At all times, he wants to be in control — of his body, of his environment — and he feared what could happen if he used.

“To each his own,” Griffey said in 2003. “If people feel they need to do certain things, that’s fine. I don’t need to do those things. My thing is, when I’m 70 and 80 years old and I’m sitting on the porch with my grandkids and those guys are long gone, that’s the important thing. You either have a short-term reward or a long-term reward.”

Getting that comment took years. Griffey made you work for interviews, which he generally loathed. Celebrities do interviews, and Griffey never saw himself that way. He had the celebrity toys, for sure, and made a lot of money from endorsements. But while he had little patience for interviews, he loved conversation and one-on-one attention.

He also liked to make you work for it. I have met few players as suspicious as Griffey, who greeted me with a sneer in September 1998 when I introduced myself as the new Mariners beat writer for The Seattle Post-Intelligencer. He promised a year of initiation before he would trust me.

I hung in there with him; Griffey was the best player on the team, so I had no choice. It was exasperating, but I learned a lot by observing him. One day, Griffey entertained the baseball team from a high school that had been ravaged by a student gunman. He had asked them to the Kingdome as his guest, but had no interest in talking about it. That was fine; the gesture said everything.

Every now and then, a young child would accompany Griffey on his pregame rounds. Most were terminally ill, and frolicking at the ballpark with Griffey was their dying wish. Sometimes they played video games with Griffey, using the Kingdome scoreboard as the screen.

You never knew which Griffey you would see before games. He joked around a lot, but he could also be in a foul mood. No matter what, though, he was genuine. As a later teammate, Bronson Arroyo of the Reds, said on Wednesday, “He was always being real.”

True to his word, a year after I started on the beat, Griffey treated me better. I asked questions, and he gave thoughtful, sometimes provocative answers. Griffey was doubtful about the direction of the Mariners, and after the 1999 season he asked for a trade, a feeling that was reinforced when his friend, the golfer Payne Stewart, was killed in a plane crash that fall. Griffey, who lived in Orlando with his wife and three children, wanted to be closer to home.

At the ’99 winter meetings, the Mariners talked with the Mets about a deal centered on Armando Benitez, Roger Cedeño and Octavio Dotel. They asked for Griffey’s approval within 15 minutes, never interpreting that as a hard deadline.

Griffey did, though, and he was deeply offended that the team would try to rush him into an important family decision. He decided to accept a trade only to the Reds, who trained in Sarasota, Fla., and had provided warm memories for him as a child.

Though his Reds career was severely marred by injuries, Griffey was warm whenever I saw him. He rarely wanted to talk about baseball. He asked about my family, I asked about his, and he remembered details, a year or more apart. Once he showed me his Blockbuster card, delighting in the name printed on it: George Gruffey, or something like that.

When Griffey bought a cellphone with video capabilities, it was all over — he regaled visitors with video clips of his sons playing football. It was his new favorite pastime, and nothing, it seemed, made him happier.

Back with the Mariners last season, Griffey looked more settled than he had seemed in years. Adored by the fans, who have always credited him for saving baseball in Seattle, Griffey made the clubhouse his playground, splicing his image into Manager Don Wakamatsu’s family photos and ramping up his needling of teammates, staffers and reporters.

Increasingly, too, he faced pitchers who idolized him growing up. In 2009, at a speaking engagement at Sacred Heart University, the Yankees’ Joba Chamberlain and the Red Sox’ Jon Lester both said that meeting Griffey was a highlight of their young careers.

“I think every kid my age wanted to be Griffey growing up,” said Lester, who was born in Tacoma, Wash., in 1984. “We played Cincinnati this year and I went up to him like a 12-year-old and asked him for an autograph and shook his hand. I think I said three words to him. I called him Mr. Ken. He kind of laughed.”

Mr. Ken has left and gone away. He never reached the World Series, and he never did pass Hank Aaron on the career home run list, finishing with 630, fifth on the list. But he honored the game, and for his generation, that is a powerful legacy. He was real.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.